O PROSTORU

ABOUT THE SPACE / prof. Marija Jenko

Notranja oblikovalka in krajinska arhitektka Petra Blaisse [1] rada tekstil sam po sebi primerja z arhitekturo, umetnostjo prostora. Zanjo je tekstil koreografija prostora [2]. Kot gibljiv element vsekakor predstavlja nasprotje stabilnemu arhitekturnemu ovoju prostora. Slednji se iz predimenzioniranega oklepa trdnjave vse bolj tanjša in se spreminja v okostju podobne zaobljene organske oblike – paličja, ki se ga mehke tekstilne opne oprimejo in se razprostrejo kot ogromna krila ptic ali kot jadra v vetru.

Tekstilna arhitektura je marsikje po svetu avtohtona oblika bivalne kulture. Prilagojena je tamkajšnjim materialom in klimatskim razmeram. V naravi se nahajajo najrazličnejše tekstilne surovine, iz katerih si prebivalci z različnimi ročnimi tekstilnimi tehnikami že od nekdaj znajo ustvariti dom. Ta arhitektura brez arhitektov je tekstilno kulturno izročilo, ki se prenaša iz roda v rod [3].

Oblikovanje samostojnih tekstilnih prostorov se je tudi tehnološko precej razvilo. Tridimenzionalne tehnologije izdelave nosilnih konstrukcij in sodobne vrste tekstilij posnemajo naravne oblike, a razvijajo se tudi različni drugi trajnostni načini, ki današnjo bivalno kulturo plemenitijo s poustvarjanjem tekstilnih tradicij. Študij oblikovanja izhaja iz preučevanja ročnih tehnik obsežnega tekstilnega izročila, zbranega od povsod. Študenti tekstilne tehnike, primerne tudi za arhitekturno rabo, preizkušajo z najrazličnejšimi naravnimi in umetnimi materiali. Prilagajajo jih svojim abstraktnim prostorskim predstavam, ki so povezane s celovitim reševanjem realnih prostorskih problematik najprej v njihovem domačem okolju.

Ta študijski pristop se je v popolni izolaciji v času epidemije COVID-19 izkazal za precej učinkovitega, saj so se študenti znašli. Naravne tekstilne surovine in vse mogoče ostanke, ki so jih našli doma, so uporabili v svojem ustvarjalnem delu, ki ravno zaradi učenja ročnih tehnik ni zamrlo. Na daljavo smo se pogovarjali o vsem, kar so študenti raziskovali, razmišljali sami pri sebi in ugotavljali v pogovorih z bližnjimi v svojem lokalnem okolju. Pridobili smo ogromno novih znanj in izkušenj.

Dejanske izkušnje s prostorom so pridobivali kar neposredno v naravi, v različnih habitatih, pri sebi doma in v bližnji urbani okolici. Prostor, ki so ga obravnavali, dopolnjevali in preoblikovali, so poznali že od otroštva. Poznali so njegovo vsebino, zgodovino, namembnost, navade in poti, z lahkoto so se poistovetili z njim.

Na novo pa so se posvetili njegovim arhitekturnim značilnostim, medsebojnim vizualnim odnosom – proporcijam med oblikami objektov ter med polnimi in praznimi delnimi prostori na izbrani lokaciji. Značilne poglede na obstoječe stanje so skicirali v perspektivi. Dokumentirali so prisotne materiale, njihove površinske teksture in barvne lestvice.

Poskušali so čim bolj ohraniti ali na novo vzpostaviti naravno ravnovesje z uporabo naravnih materialov za prostorske tekstilne intervencije, s katerimi so ustvarjali boljše pogoje za bivanje. Z njimi so povezovali notranjosti in zunanjosti zgradb. Iskali so tekstilne izboljšave za različne potrebe, na primer za naravno ventilacijo ali pasivno hlajenje stavb. Za zgled so jim bile tradicionalne bivanjske navade in načini arhitekturnega oblikovanja, značilni za njihova domača okolja.

Primerjali so jih z drugimi tovrstnimi tradicijami, na primer z japonsko, ki je imela velik vpliv na nastanek modernizma in tudi na biorealistično arhitekturo Richarda Neutre [4]. Njegov pristop k prilagajanju lokalnim okoljskim in drugim razmeram je študente navdušil. Arhitekt se je počutil kot zdravnik, ki je s preiskovanjem svojih strank ugotavljal njihove potrebe in jim naposled predpisal arhitekturni odgovor zanje.

V njihov preiskovalni karton, kjer je zbral celotno zgodovino pacienta, je vedno dodal opombo, ali naj se ta odgovor izdela v načrtu, prerezu ali fasadi. Nadvse sodobno in trajnostno pa je bilo tudi njegovo zavzemanje za generična bivališča, le teoretično po japonskem vzoru, ki so optimirana z okolju prijazno in varčno sodobno tehnologijo.

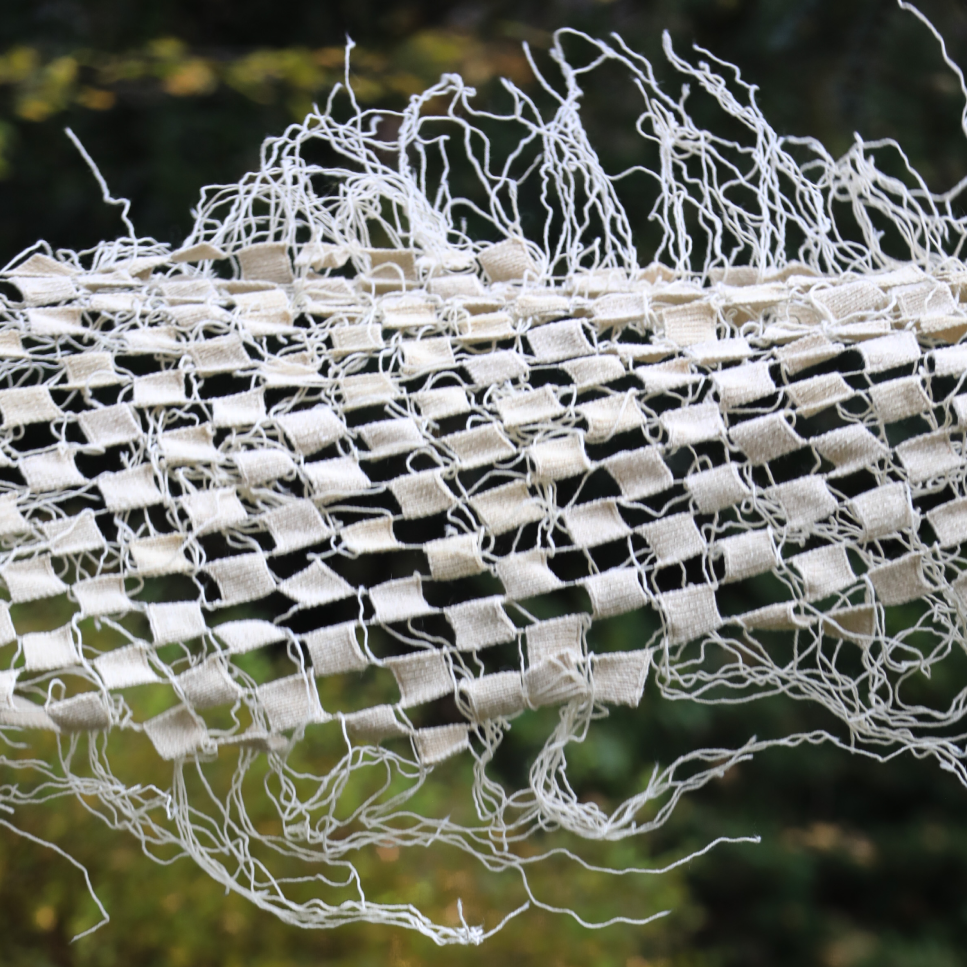

Prostor je nedvomno najbolj vsestranska tematika, v kateri se oblikovanje tekstilij povezuje z drugimi umetniškimi in znanstvenimi področji. Tekstilije s tem postanejo prostorotvorne. Prostor poudari njihovo strukturo, prosojnost in barvitost ter jih osvobodi njihove ploskovite ukleščenosti. Izkoristi jo kot gradnik – za kožo prostorskih form, v katere so tekstilije vpete z vseh strani, da so povsem gladko napete kot bobni; ali pa so tekstilne oblike pritrjene samo na določenih mestih, da imajo možnost najrazličnejših gibanj v prostoru kot plesalke, ki Petro Blaisse vedno znova navdušijo, da se z njimi spusti v njej že pričakovano prostorsko avanturo.

Viri:

[1] Blaisse, Petra. Inside Outside, Nai Publishers, Rotterdam, 2009

[2] Krüger, Sylvie. Textile Architecture, Jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2009

[3] Rudofsky, Bernard. Arhitektura bez arhitekata, Građevinska knjiga, Beograd, 1976

[4] Morse, B. C. Richard Neutra, Biorealist, magistrsko delo (mentor: Long, Christopher), University of Texas at Austin, 2013

Tekstilna arhitektura je marsikje po svetu avtohtona oblika bivalne kulture. Prilagojena je tamkajšnjim materialom in klimatskim razmeram. V naravi se nahajajo najrazličnejše tekstilne surovine, iz katerih si prebivalci z različnimi ročnimi tekstilnimi tehnikami že od nekdaj znajo ustvariti dom. Ta arhitektura brez arhitektov je tekstilno kulturno izročilo, ki se prenaša iz roda v rod [3].

Oblikovanje samostojnih tekstilnih prostorov se je tudi tehnološko precej razvilo. Tridimenzionalne tehnologije izdelave nosilnih konstrukcij in sodobne vrste tekstilij posnemajo naravne oblike, a razvijajo se tudi različni drugi trajnostni načini, ki današnjo bivalno kulturo plemenitijo s poustvarjanjem tekstilnih tradicij. Študij oblikovanja izhaja iz preučevanja ročnih tehnik obsežnega tekstilnega izročila, zbranega od povsod. Študenti tekstilne tehnike, primerne tudi za arhitekturno rabo, preizkušajo z najrazličnejšimi naravnimi in umetnimi materiali. Prilagajajo jih svojim abstraktnim prostorskim predstavam, ki so povezane s celovitim reševanjem realnih prostorskih problematik najprej v njihovem domačem okolju.

Ta študijski pristop se je v popolni izolaciji v času epidemije COVID-19 izkazal za precej učinkovitega, saj so se študenti znašli. Naravne tekstilne surovine in vse mogoče ostanke, ki so jih našli doma, so uporabili v svojem ustvarjalnem delu, ki ravno zaradi učenja ročnih tehnik ni zamrlo. Na daljavo smo se pogovarjali o vsem, kar so študenti raziskovali, razmišljali sami pri sebi in ugotavljali v pogovorih z bližnjimi v svojem lokalnem okolju. Pridobili smo ogromno novih znanj in izkušenj.

Dejanske izkušnje s prostorom so pridobivali kar neposredno v naravi, v različnih habitatih, pri sebi doma in v bližnji urbani okolici. Prostor, ki so ga obravnavali, dopolnjevali in preoblikovali, so poznali že od otroštva. Poznali so njegovo vsebino, zgodovino, namembnost, navade in poti, z lahkoto so se poistovetili z njim.

Na novo pa so se posvetili njegovim arhitekturnim značilnostim, medsebojnim vizualnim odnosom – proporcijam med oblikami objektov ter med polnimi in praznimi delnimi prostori na izbrani lokaciji. Značilne poglede na obstoječe stanje so skicirali v perspektivi. Dokumentirali so prisotne materiale, njihove površinske teksture in barvne lestvice.

Poskušali so čim bolj ohraniti ali na novo vzpostaviti naravno ravnovesje z uporabo naravnih materialov za prostorske tekstilne intervencije, s katerimi so ustvarjali boljše pogoje za bivanje. Z njimi so povezovali notranjosti in zunanjosti zgradb. Iskali so tekstilne izboljšave za različne potrebe, na primer za naravno ventilacijo ali pasivno hlajenje stavb. Za zgled so jim bile tradicionalne bivanjske navade in načini arhitekturnega oblikovanja, značilni za njihova domača okolja.

Primerjali so jih z drugimi tovrstnimi tradicijami, na primer z japonsko, ki je imela velik vpliv na nastanek modernizma in tudi na biorealistično arhitekturo Richarda Neutre [4]. Njegov pristop k prilagajanju lokalnim okoljskim in drugim razmeram je študente navdušil. Arhitekt se je počutil kot zdravnik, ki je s preiskovanjem svojih strank ugotavljal njihove potrebe in jim naposled predpisal arhitekturni odgovor zanje.

V njihov preiskovalni karton, kjer je zbral celotno zgodovino pacienta, je vedno dodal opombo, ali naj se ta odgovor izdela v načrtu, prerezu ali fasadi. Nadvse sodobno in trajnostno pa je bilo tudi njegovo zavzemanje za generična bivališča, le teoretično po japonskem vzoru, ki so optimirana z okolju prijazno in varčno sodobno tehnologijo.

Prostor je nedvomno najbolj vsestranska tematika, v kateri se oblikovanje tekstilij povezuje z drugimi umetniškimi in znanstvenimi področji. Tekstilije s tem postanejo prostorotvorne. Prostor poudari njihovo strukturo, prosojnost in barvitost ter jih osvobodi njihove ploskovite ukleščenosti. Izkoristi jo kot gradnik – za kožo prostorskih form, v katere so tekstilije vpete z vseh strani, da so povsem gladko napete kot bobni; ali pa so tekstilne oblike pritrjene samo na določenih mestih, da imajo možnost najrazličnejših gibanj v prostoru kot plesalke, ki Petro Blaisse vedno znova navdušijo, da se z njimi spusti v njej že pričakovano prostorsko avanturo.

Viri:

[1] Blaisse, Petra. Inside Outside, Nai Publishers, Rotterdam, 2009

[2] Krüger, Sylvie. Textile Architecture, Jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2009

[3] Rudofsky, Bernard. Arhitektura bez arhitekata, Građevinska knjiga, Beograd, 1976

[4] Morse, B. C. Richard Neutra, Biorealist, magistrsko delo (mentor: Long, Christopher), University of Texas at Austin, 2013

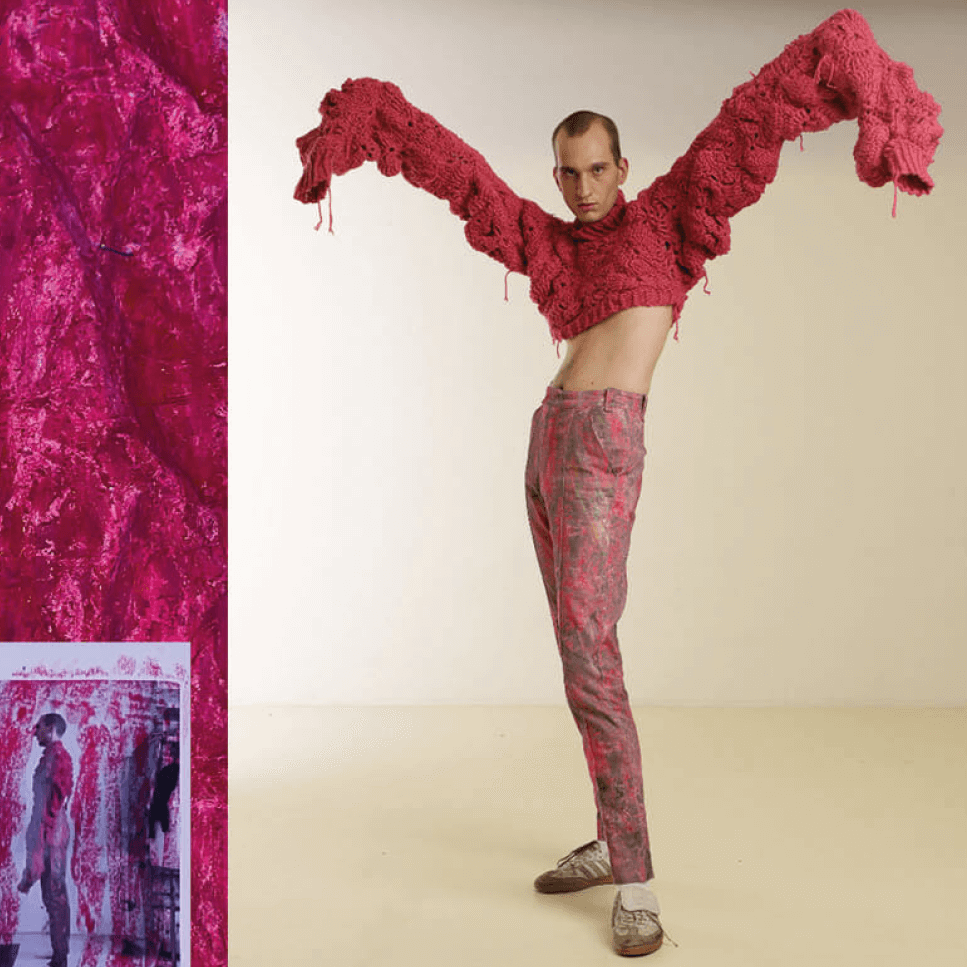

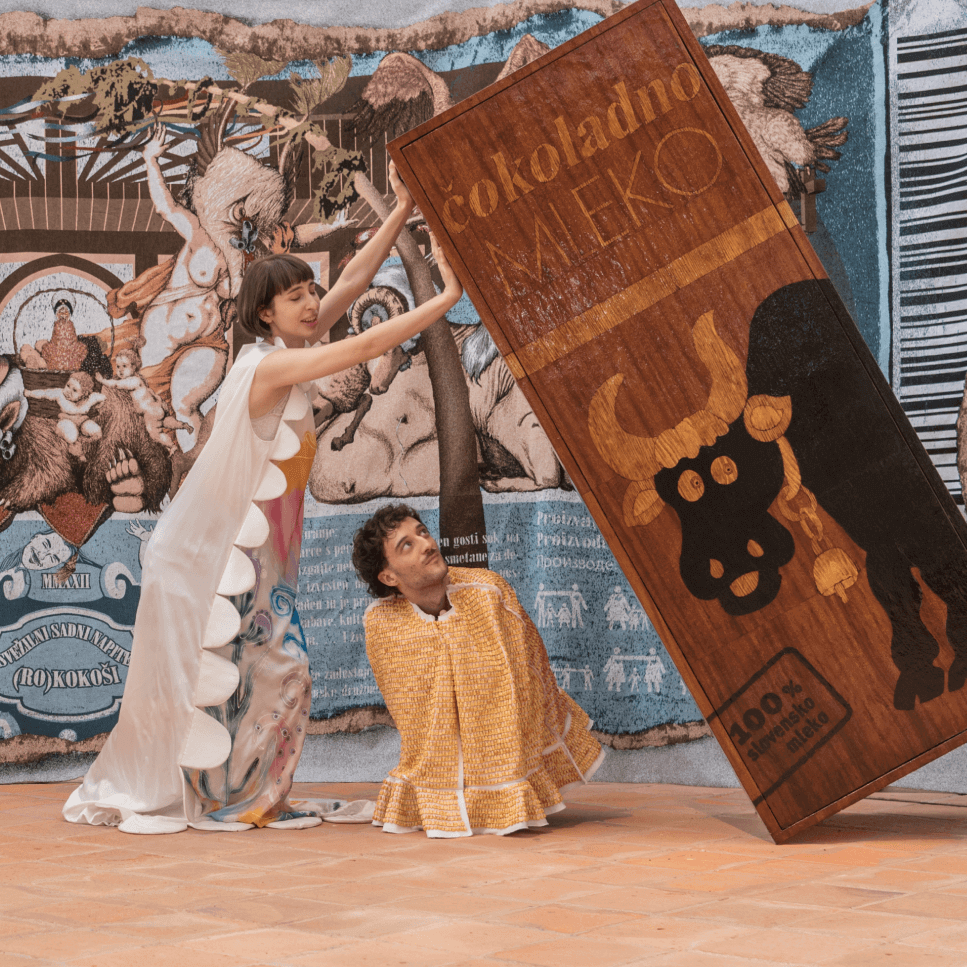

The interior designer and landscape architect Petra Blaisse [1] likes to compare textile to architecture, the art of space. For her, textile is the choreography of space [2]. As a moving element, it represents the opposite of the solid architectural envelope of the space. The latter becomes thinner and thinner, and from the oversized armour of the fortress, it transforms into a skeleton-like rounded organic form - sticks, to which the soft textile membranes cling and spread out like enormous bird wings or like sails in the wind.

Textile architecture is an indigenous form of living culture in many parts of the world. It adapts to the local materials and climatic conditions. Various raw textile materials can be found in nature, from which the inhabitants have always been able to create a home using different hand textile techniques. This architecture without architects is a textile cultural heritage that is passed down from generation to generation [3].

The design of independent textile spaces has also undergone significant technological development. Three-dimensional technologies for the production of load-bearing structures and modern types of textiles imitate natural forms. Various other sustainable methods are also being developed, enriching today’s living culture by recreating textile traditions. The study of design comes from studying the hand techniques of a vast textile tradition gathered from everywhere. Students use textile techniques that are also suitable for architectural use and test them with a wide variety of natural and artificial materials. They adapt them to their abstract spatial concepts, which are connected with the comprehensive solution of real spatial problems in their home environment.

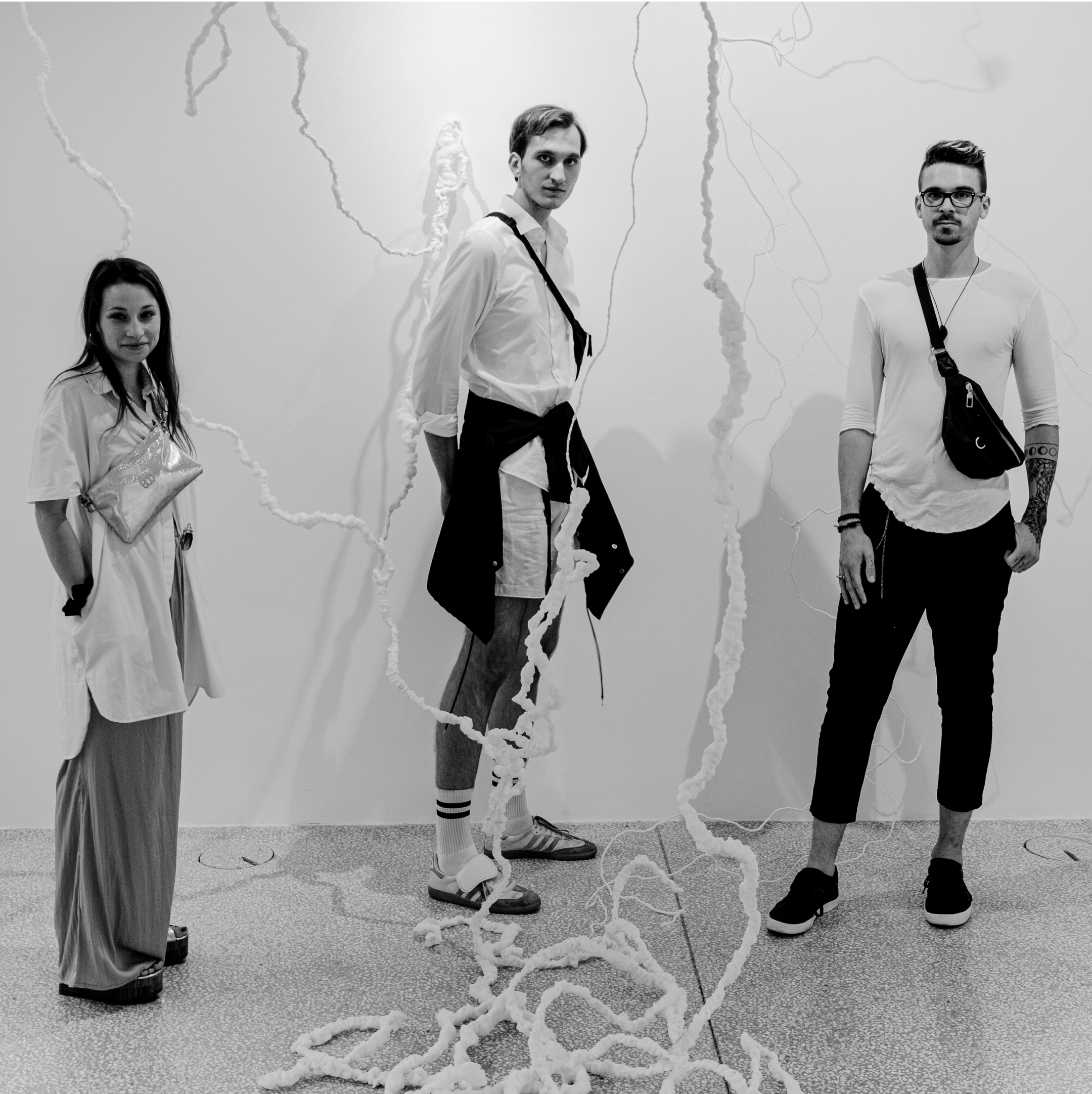

This study approach proved effective in complete isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic, as students quickly adapted. They used natural textile materials and all possible remnants found at home for their creative work, which, precisely due to the learning of hand techniques, did not stagnate. We discussed remotely about everything that students researched, pondered and found out in conversations with those close to them in their local environment. We gained a lot of new knowledge and experiences.

They gained experience with space directly in nature, in different habitats, at home and in the nearby urban environment. The space they discussed, complemented and transformed was familiar to them since childhood. They knew its content, history, purpose, habits and ways and easily identified with it. However, they focused anew on its architectural features and mutual visual relationships - the proportions between the shapes of the buildings and between the full and empty spaces at the selected location. They sketched characteristic views of the existing situation in perspective and documented the materials present, their surface textures and colour scales.

They tried to preserve or restore the natural balance as much as possible by using natural materials for spatial textile interventions, which created better living conditions. These interventions connected the interiors and exteriors of buildings. Textile improvements were sought for various needs, such as natural ventilation or passive cooling of buildings. Students took inspiration from traditional living habits and methods of architectural design characteristic of their local environments. They compared them with other traditions, such as Japanese, which had a significant influence on the emergence of modernism and architecture of biorealist Richard Neutra [4]. His approach to adapting to local environmental and other conditions impressed the students. The architect felt like a doctor who, by examining his clients, determined their needs and finally prescribed an architectural answer for them. In their dossier, where he collected the patient’s entire history, he always noted whether this answer should be made as a plan, section or façade. His advocacy for generic dwellings, theoretically following the Japanese model, optimised with environmentally friendly and economically efficient modern technology, was also remarkably contemporary and sustainable.

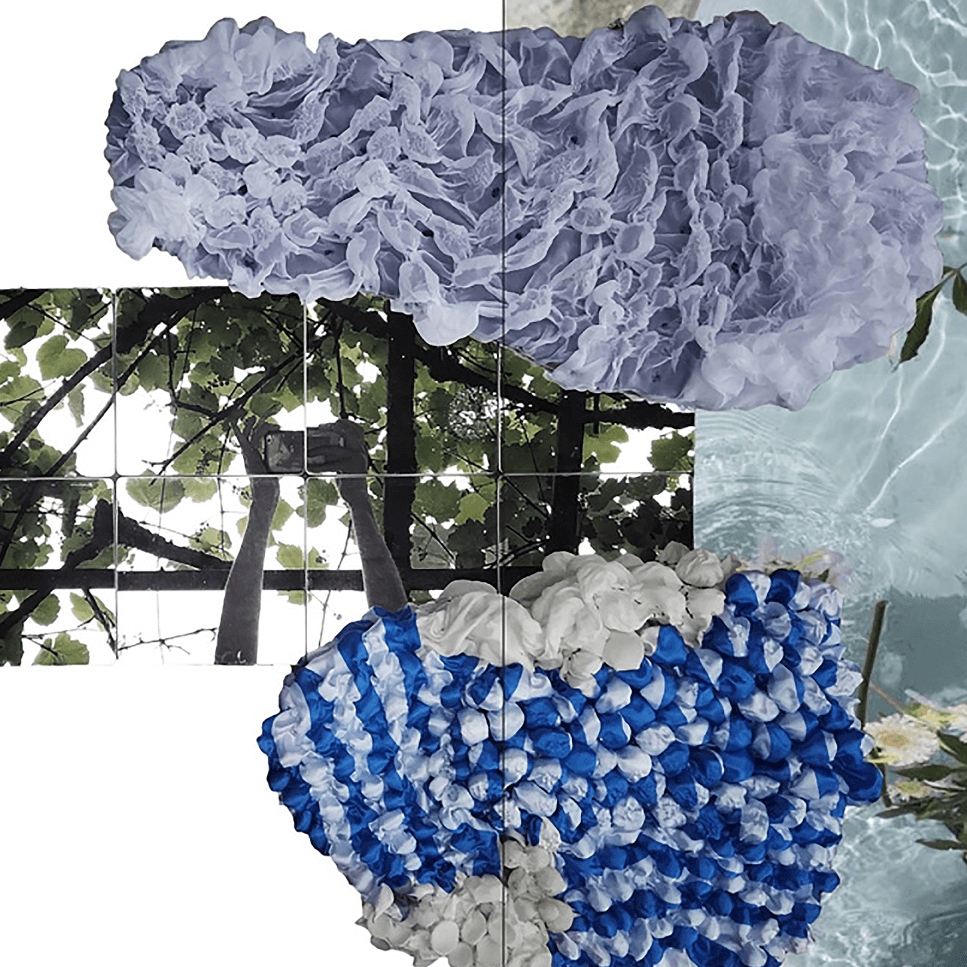

Space is undoubtedly the most versatile topic in which textile design is connected to other artistic and scientific fields. Textiles thus become space-creating. Space accentuates their structure, transparency and colourfulness, and liberates them from their two-dimensional constraints. It uses them as building blocks - for the skin of spatial forms in which textiles are clamped from all sides, stretched smoothly like drums. Or the textile shapes are attached only at certain points, allowing them a variety of movements in space, like dancers that repeatedly inspire Petra Blaisse to embark on the spatial adventure.

Bibliography:

[1] Blaisse, Petra. Inside Outside, Nai Publishers, Rotterdam, 2009

[2] Krüger, Sylvie. Textile Architecture, Jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2009

[3] Rudofsky, Bernard. Arhitektura bez arhitekata, Građevinska knjiga, Beograd, 1976

[4] Morse, B. C. Richard Neutra, Biorealist, Master thesis (supevisor: Long, Christopher), University of Texas at Austin, 2013

Textile architecture is an indigenous form of living culture in many parts of the world. It adapts to the local materials and climatic conditions. Various raw textile materials can be found in nature, from which the inhabitants have always been able to create a home using different hand textile techniques. This architecture without architects is a textile cultural heritage that is passed down from generation to generation [3].

The design of independent textile spaces has also undergone significant technological development. Three-dimensional technologies for the production of load-bearing structures and modern types of textiles imitate natural forms. Various other sustainable methods are also being developed, enriching today’s living culture by recreating textile traditions. The study of design comes from studying the hand techniques of a vast textile tradition gathered from everywhere. Students use textile techniques that are also suitable for architectural use and test them with a wide variety of natural and artificial materials. They adapt them to their abstract spatial concepts, which are connected with the comprehensive solution of real spatial problems in their home environment.

This study approach proved effective in complete isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic, as students quickly adapted. They used natural textile materials and all possible remnants found at home for their creative work, which, precisely due to the learning of hand techniques, did not stagnate. We discussed remotely about everything that students researched, pondered and found out in conversations with those close to them in their local environment. We gained a lot of new knowledge and experiences.

They gained experience with space directly in nature, in different habitats, at home and in the nearby urban environment. The space they discussed, complemented and transformed was familiar to them since childhood. They knew its content, history, purpose, habits and ways and easily identified with it. However, they focused anew on its architectural features and mutual visual relationships - the proportions between the shapes of the buildings and between the full and empty spaces at the selected location. They sketched characteristic views of the existing situation in perspective and documented the materials present, their surface textures and colour scales.

They tried to preserve or restore the natural balance as much as possible by using natural materials for spatial textile interventions, which created better living conditions. These interventions connected the interiors and exteriors of buildings. Textile improvements were sought for various needs, such as natural ventilation or passive cooling of buildings. Students took inspiration from traditional living habits and methods of architectural design characteristic of their local environments. They compared them with other traditions, such as Japanese, which had a significant influence on the emergence of modernism and architecture of biorealist Richard Neutra [4]. His approach to adapting to local environmental and other conditions impressed the students. The architect felt like a doctor who, by examining his clients, determined their needs and finally prescribed an architectural answer for them. In their dossier, where he collected the patient’s entire history, he always noted whether this answer should be made as a plan, section or façade. His advocacy for generic dwellings, theoretically following the Japanese model, optimised with environmentally friendly and economically efficient modern technology, was also remarkably contemporary and sustainable.

Space is undoubtedly the most versatile topic in which textile design is connected to other artistic and scientific fields. Textiles thus become space-creating. Space accentuates their structure, transparency and colourfulness, and liberates them from their two-dimensional constraints. It uses them as building blocks - for the skin of spatial forms in which textiles are clamped from all sides, stretched smoothly like drums. Or the textile shapes are attached only at certain points, allowing them a variety of movements in space, like dancers that repeatedly inspire Petra Blaisse to embark on the spatial adventure.

Bibliography:

[1] Blaisse, Petra. Inside Outside, Nai Publishers, Rotterdam, 2009

[2] Krüger, Sylvie. Textile Architecture, Jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2009

[3] Rudofsky, Bernard. Arhitektura bez arhitekata, Građevinska knjiga, Beograd, 1976

[4] Morse, B. C. Richard Neutra, Biorealist, Master thesis (supevisor: Long, Christopher), University of Texas at Austin, 2013