TEKSTIL GRE SKOZI ROKE

Razmišljanje o izkušnji pandemije na rokodelske veščine študentov oblikovanja tekstilij / izr. prof. mag. Katja Burger Kovič

TEXTILE PASSES THROUGH THE HANDS - reflection on the impact of the pandemic on the handicraft skills of textile design students / Assoc. Prof. Katja Burger Kovič

Čeprav je sodobno oblikovanje v človeški zgodovini mlada stroka in sega v začetek industrijske revolucije, je prešlo že mnogo faz razvoja – od izdelave prvih serijskih izdelkov pa vse do virtualnega oblikovanja.

Oblikovanje je osvojilo občutek za funkcijo, dekoracijo, obliko, material in barvo, pa tudi za ime, logotip in blagovno znamko. Izdelki se proizvajajo in prodajajo na globalnem trgu, ki izgleda kot svet neskončnih možnosti in vedno novih, še boljših izdelkov.

Oblikovanje 'novega' je ekspanziralo in postalo nenasitno predvsem v zadnjih desetletjih. Človek je svet napolnil z izdelki, ki ponujajo nova in nova doživetja, vendar velikokrat brez prave vsebine in značaja. Svetovno priznana napovedovalka trendov Lidewij Edelkoort (1) pravi, da danes bolj kot kdajkoli poprej oblikovanje potrebuje refleksijo – ponoven razmislek o (ne)smislu oblikovanja, v ta razmislek pa moramo vključiti tudi človečnost.

Zanjo obrt in ročno narejeni izdelki predstavljajo možne alternative, h katerim se v svojem kreativnem procesu vračajo mnogi oblikovalci in umetniki (2).Edelkoortova je zgornje besede zapisala leta 2014, kar nekaj let pred pandemijo covid-19. Vse večja uporaba digitalnih medijev, virtualnega fantazijskega sveta ter umetne inteligence, ki je v času pandemije eksponentno narasla, je po drugi strani sprožila revolucijo taktilnega, potrebo po ročnem delu ter oživitvi izkušnje oblike in volumna preko fizičnega dotika – občutljivega mehanizma zaznave sveta skozi naše roke.Popularizacija 'novega vala' ročnega dela se je v ZDA začela že leta 1994. Dandanes predstavlja t. i. 'indie craft scene' (3) svojevrstno mešanico tradicionalnih tehnik ročnega dela, punkovske kulture, DIY (4) etosa, moderne estetike, politike, feminizma in umetnosti. Gibanje, ki je postalo globalno, je v svojem bistvu močno povezano s skupnostjo – tako lokalno ali povezano preko svetovnega spleta –, ki velikokrat sproža nove ekonomske odnose in način življenja, osnovan na kreativnosti in mreženju. Andrew Wagner zapiše, da rokodelstvo ne govori samo o načinu izdelave ter kvaliteti časa in truda vloženega v nastanek izdelka, ampak ima lahko tudi politični glas (Wagner, 2008, 3).

Ročno delo, njegova ponovna kvaliteta je bila dvignjena in prepoznana v zadnjih dvajsetih letih tudi zaradi kopice t. i. 'Slow' (počasen) gibanj, iz katerih je izšlo tudi Slow design gibanje, katerega termin je prvič zapisal Alistair Fuad-Luke leta 2002.

Gibanje je obravnavalo holističen pristop k oblikovanju in se je – tako kot se je v zgodovini oblikovanja že mnogokrat poprej – zavzemalo za proces dela, ki vzame v obzir dobro človeka, družbe in okolja. Gibanje pa se je poleg izdelovanja fizičnih izdelkov preselilo tudi na nematerialno oblikovanje – oblikovanje procesov, storitev, izkušenj, organizacij in gre dandanes naprej v polje dematerializacije.

Svetovna recesija leta 2008 je med drugim prinesla ponovno prevetritev vrednot, procesa oblikovalskega dela in možnosti trženja izdelkov. Ti niso več pogojeni samo z naročili večjih podjetij in blagovnih znamk, ampak začenjajo nastajati izpod rok manjših oblikovalskih studiev, rokodelskih podjetij in velikokrat zrastejo iz potrebe skupnosti.

Rokodelstvo, vklučevanje procesa ročnega dela v končni izdelek, igra tu veliko vlogo. Pri oblikovalcu ni več samo del eksperimentalnega nastajanja nove ideje, ampak se le-ta integrira v samo proizvodnjo. Človeška roka dobi novo moč in postane del orodja.

Oziroma kot poetično zapiše Juhani Pallasmaa: »... kadar vešč uporabnik uporablja sekiro ali nož, o roki in orodju ne razmišlja kot o dveh različnih in ločenih entitetah; orodje je postalo del roke, spremenilo jo je v popolnoma novo vrsto organov, v orodje-roko.« (Pallasmaa, 2009,54).

Knjigo On Craftsmanship towards a new Bauhaus začne avtor Christopher Frayling s stavkom, da je rokodelstvo postalo modno med vsemi zadnjimi večjimi recesijami, zato ta termin potrebujemo v današnjem času ponovno definirati in evalvirati (Frayling, 2010, 7). Rokodelstvo, med njimi specifično tudi tekstilne ročne tehnike, postajajo (ponovno) pomembne tudi v času podnebne, migrantske, postpandemične ekonmske krize, v kateri živimo danes in v kateri si skuša nova generacija Z najti svoje mesto na Zemlji, poiskati možnosti, kako ne samo preživeti, ampak tudi kreativno soustvarjati prihodnost, ki ne izgublja stika s tradicijo.

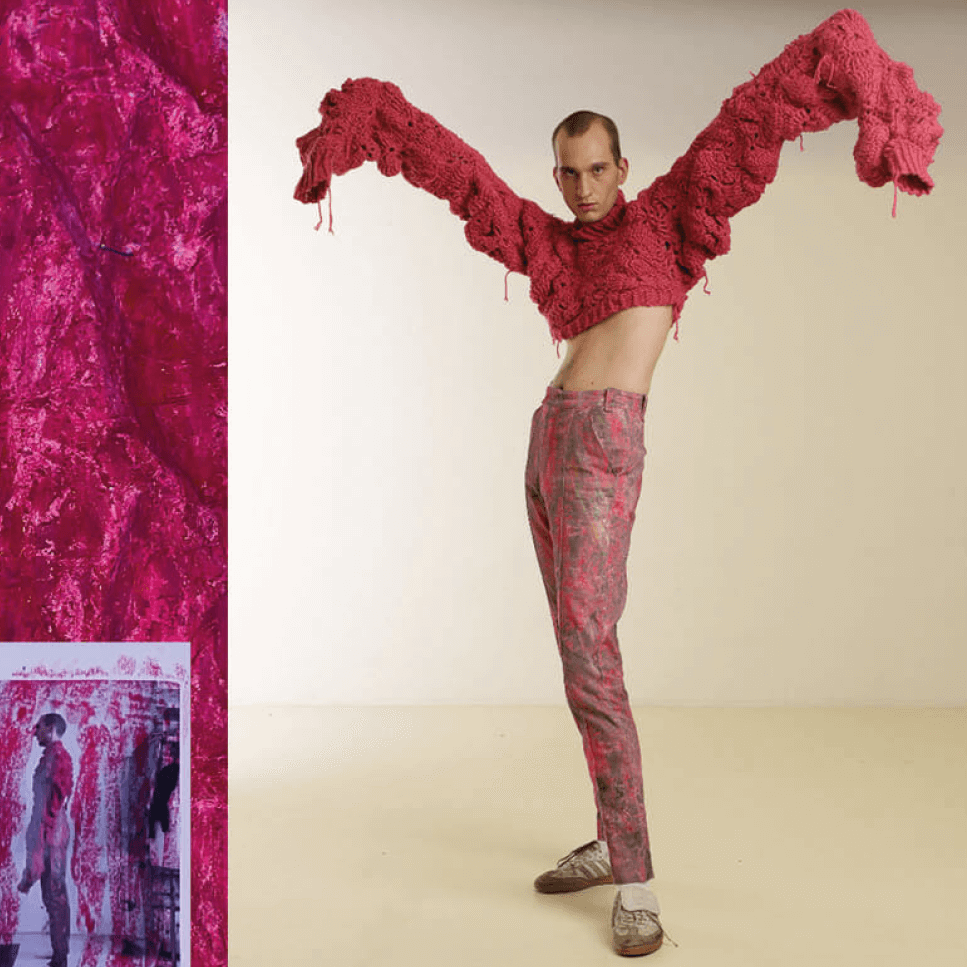

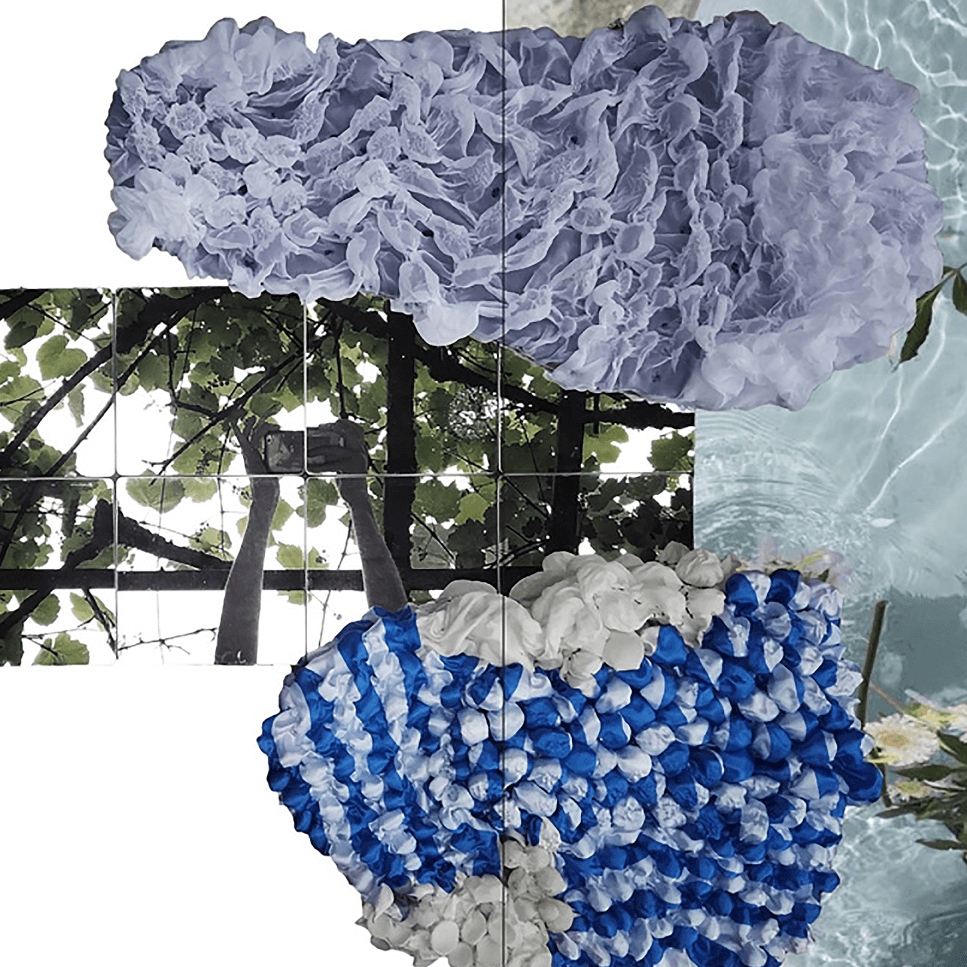

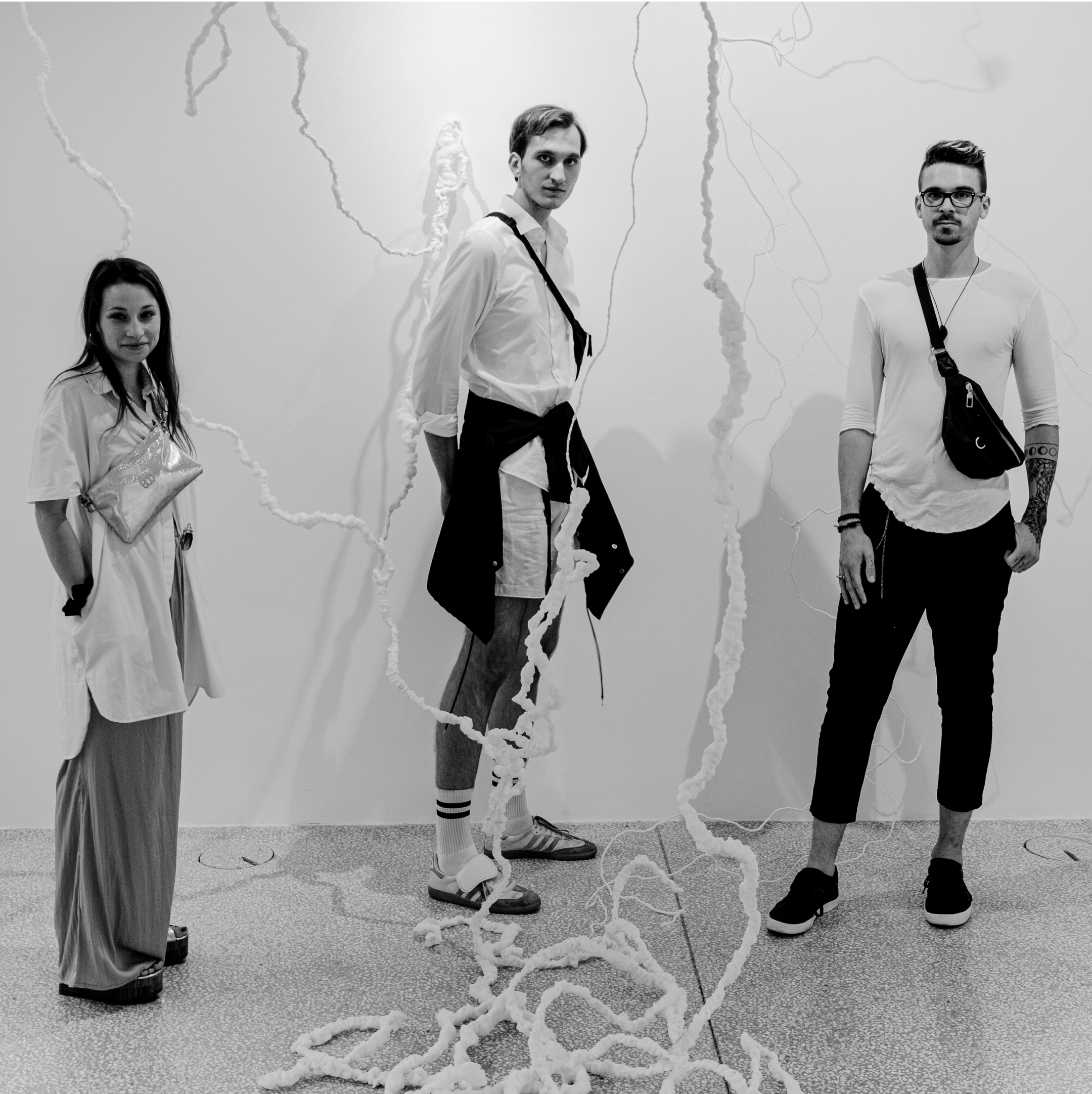

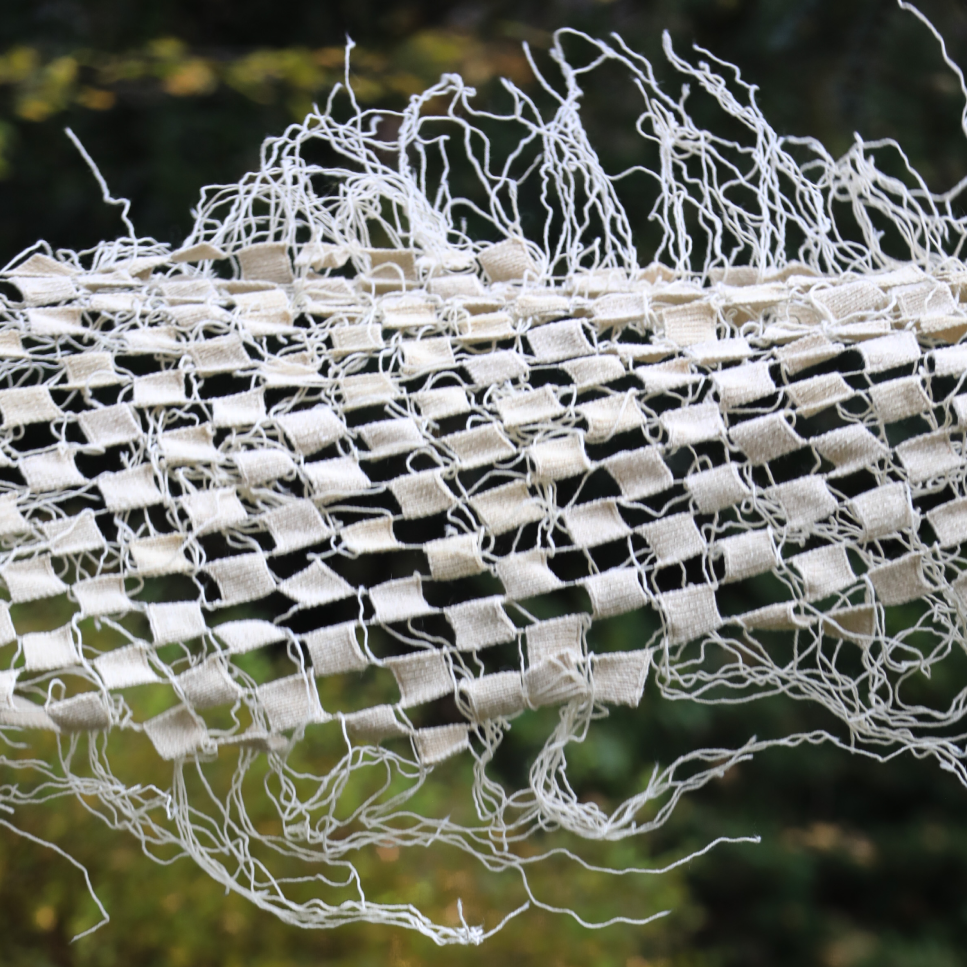

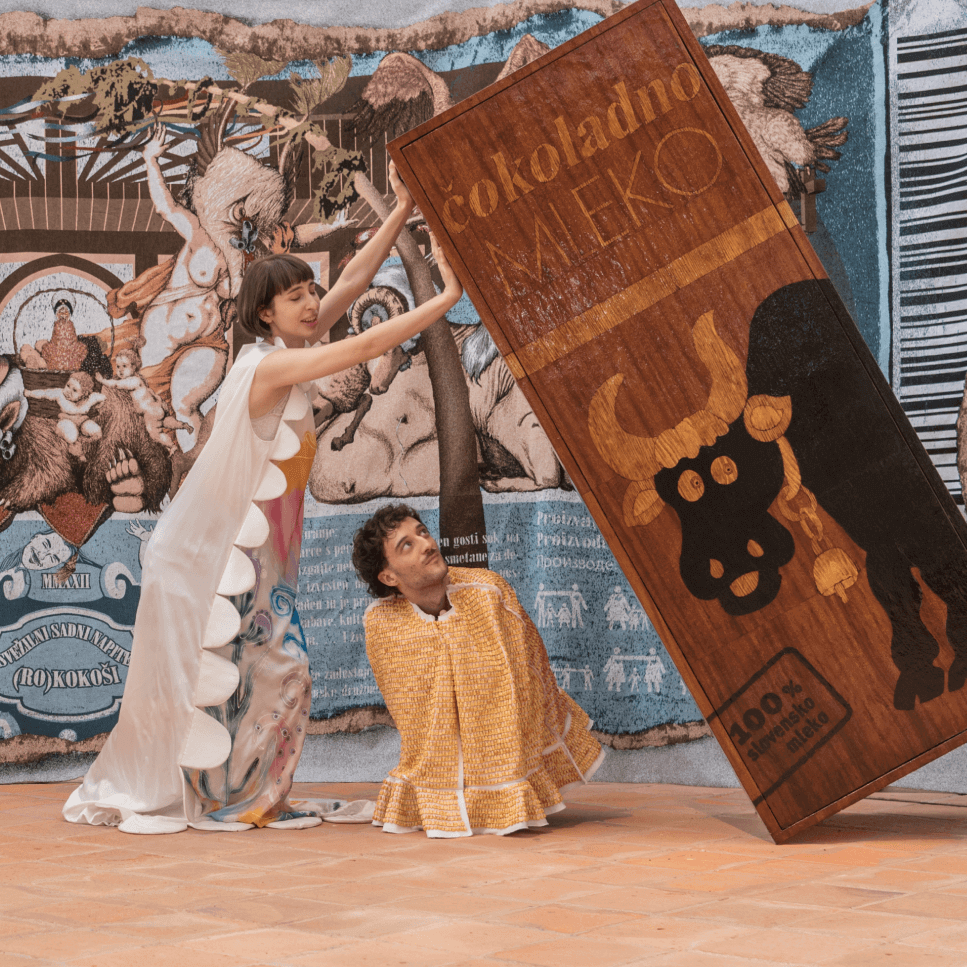

V obdobju, ko smo bili primorani ustvarjalne pedagoške procese vodenega mentoriranja pri predmetih Oblikovanje tekstilij na prvi in drugi stopnji študija Oblikovanje tekstilij in oblačil izvajati 'na daljavo', smo bili odrezani od fizičnega stika s tekstilijo, ki je nastajala izpod rok študenta, navkljub temu pa smo bili priča novonastalemu naravnemu ritmu doma izdelane tkanine, pletiva, kvačkanine, ki spodbuja 'počasno', ročno izdelovanje, osmišlja možnosti maloserijske produkcije in ponuja nove načine promocije izdelkov.

Utrdili smo pot trajnostnemu oblikovanju, ekologiji, lokalni produkciji, vrnili smo se k naravnim materialom, ekološkim barvilom, poobdelavam ter obrtniškemu znanju in tradicionalnim tehnikam izdelave.

Kreativnost posameznika ni zamrla, nasprotno, spregledano ročno delo z nitjo, prejo, tekstilijo je postalo na novo odkrito in prepoznano, kot pogled na pokrajino, ko izstopimo iz brzečega se vozila. In nekaj od te izkušnje se je brez dvoma zapisalo v gene te 'covidne' generacije študentov. Vsaka težka izkušnja ponuja priložnosti, da prevetirmo utečene vzorce delovanja in naredimo potrebne spremembe.

Oblikovanje je osvojilo občutek za funkcijo, dekoracijo, obliko, material in barvo, pa tudi za ime, logotip in blagovno znamko. Izdelki se proizvajajo in prodajajo na globalnem trgu, ki izgleda kot svet neskončnih možnosti in vedno novih, še boljših izdelkov.

Oblikovanje 'novega' je ekspanziralo in postalo nenasitno predvsem v zadnjih desetletjih. Človek je svet napolnil z izdelki, ki ponujajo nova in nova doživetja, vendar velikokrat brez prave vsebine in značaja. Svetovno priznana napovedovalka trendov Lidewij Edelkoort (1) pravi, da danes bolj kot kdajkoli poprej oblikovanje potrebuje refleksijo – ponoven razmislek o (ne)smislu oblikovanja, v ta razmislek pa moramo vključiti tudi človečnost.

Zanjo obrt in ročno narejeni izdelki predstavljajo možne alternative, h katerim se v svojem kreativnem procesu vračajo mnogi oblikovalci in umetniki (2).Edelkoortova je zgornje besede zapisala leta 2014, kar nekaj let pred pandemijo covid-19. Vse večja uporaba digitalnih medijev, virtualnega fantazijskega sveta ter umetne inteligence, ki je v času pandemije eksponentno narasla, je po drugi strani sprožila revolucijo taktilnega, potrebo po ročnem delu ter oživitvi izkušnje oblike in volumna preko fizičnega dotika – občutljivega mehanizma zaznave sveta skozi naše roke.Popularizacija 'novega vala' ročnega dela se je v ZDA začela že leta 1994. Dandanes predstavlja t. i. 'indie craft scene' (3) svojevrstno mešanico tradicionalnih tehnik ročnega dela, punkovske kulture, DIY (4) etosa, moderne estetike, politike, feminizma in umetnosti. Gibanje, ki je postalo globalno, je v svojem bistvu močno povezano s skupnostjo – tako lokalno ali povezano preko svetovnega spleta –, ki velikokrat sproža nove ekonomske odnose in način življenja, osnovan na kreativnosti in mreženju. Andrew Wagner zapiše, da rokodelstvo ne govori samo o načinu izdelave ter kvaliteti časa in truda vloženega v nastanek izdelka, ampak ima lahko tudi politični glas (Wagner, 2008, 3).

Ročno delo, njegova ponovna kvaliteta je bila dvignjena in prepoznana v zadnjih dvajsetih letih tudi zaradi kopice t. i. 'Slow' (počasen) gibanj, iz katerih je izšlo tudi Slow design gibanje, katerega termin je prvič zapisal Alistair Fuad-Luke leta 2002.

Gibanje je obravnavalo holističen pristop k oblikovanju in se je – tako kot se je v zgodovini oblikovanja že mnogokrat poprej – zavzemalo za proces dela, ki vzame v obzir dobro človeka, družbe in okolja. Gibanje pa se je poleg izdelovanja fizičnih izdelkov preselilo tudi na nematerialno oblikovanje – oblikovanje procesov, storitev, izkušenj, organizacij in gre dandanes naprej v polje dematerializacije.

Svetovna recesija leta 2008 je med drugim prinesla ponovno prevetritev vrednot, procesa oblikovalskega dela in možnosti trženja izdelkov. Ti niso več pogojeni samo z naročili večjih podjetij in blagovnih znamk, ampak začenjajo nastajati izpod rok manjših oblikovalskih studiev, rokodelskih podjetij in velikokrat zrastejo iz potrebe skupnosti.

Rokodelstvo, vklučevanje procesa ročnega dela v končni izdelek, igra tu veliko vlogo. Pri oblikovalcu ni več samo del eksperimentalnega nastajanja nove ideje, ampak se le-ta integrira v samo proizvodnjo. Človeška roka dobi novo moč in postane del orodja.

Oziroma kot poetično zapiše Juhani Pallasmaa: »... kadar vešč uporabnik uporablja sekiro ali nož, o roki in orodju ne razmišlja kot o dveh različnih in ločenih entitetah; orodje je postalo del roke, spremenilo jo je v popolnoma novo vrsto organov, v orodje-roko.« (Pallasmaa, 2009,54).

Knjigo On Craftsmanship towards a new Bauhaus začne avtor Christopher Frayling s stavkom, da je rokodelstvo postalo modno med vsemi zadnjimi večjimi recesijami, zato ta termin potrebujemo v današnjem času ponovno definirati in evalvirati (Frayling, 2010, 7). Rokodelstvo, med njimi specifično tudi tekstilne ročne tehnike, postajajo (ponovno) pomembne tudi v času podnebne, migrantske, postpandemične ekonmske krize, v kateri živimo danes in v kateri si skuša nova generacija Z najti svoje mesto na Zemlji, poiskati možnosti, kako ne samo preživeti, ampak tudi kreativno soustvarjati prihodnost, ki ne izgublja stika s tradicijo.

V obdobju, ko smo bili primorani ustvarjalne pedagoške procese vodenega mentoriranja pri predmetih Oblikovanje tekstilij na prvi in drugi stopnji študija Oblikovanje tekstilij in oblačil izvajati 'na daljavo', smo bili odrezani od fizičnega stika s tekstilijo, ki je nastajala izpod rok študenta, navkljub temu pa smo bili priča novonastalemu naravnemu ritmu doma izdelane tkanine, pletiva, kvačkanine, ki spodbuja 'počasno', ročno izdelovanje, osmišlja možnosti maloserijske produkcije in ponuja nove načine promocije izdelkov.

Utrdili smo pot trajnostnemu oblikovanju, ekologiji, lokalni produkciji, vrnili smo se k naravnim materialom, ekološkim barvilom, poobdelavam ter obrtniškemu znanju in tradicionalnim tehnikam izdelave.

Kreativnost posameznika ni zamrla, nasprotno, spregledano ročno delo z nitjo, prejo, tekstilijo je postalo na novo odkrito in prepoznano, kot pogled na pokrajino, ko izstopimo iz brzečega se vozila. In nekaj od te izkušnje se je brez dvoma zapisalo v gene te 'covidne' generacije študentov. Vsaka težka izkušnja ponuja priložnosti, da prevetirmo utečene vzorce delovanja in naredimo potrebne spremembe.

OPOMBE:

1. Lidewij Edelkoort je svetovno priznana napovedovalka trendov. Več o njej in njenih tekstih o trendih, oblikovanju pa tudi vlogi rokodelstva v sodobnem času si lahko preberemo na njeni socialnomedijski platformi: http://www.edelkoort.com/trendtablet/

2. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Handmade -When Design and Craft meet, 2013, dostopno na: http://www.trendtablet.com/4810-handmade/ (26.2.2014)

3. 'Indie' je okrajšava za 'indipendant' , lahko bi zapisali tudi 'neodvisna rokodelska skupnost'.

4. DIY je angleška kratica za: Do It Yourself, slovensko naredi si sam

5. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Crafts, a matter of scale and pace, 2014, dostopno na: http://www.trendtablet.com/29499-crafts-a-matter-of-scale-and-pace/ (26.2.2014)

LITERATURA:

Levine,Faythe in Heimerl, Cortney (ur.), Handmade nation: the rise of DIY, art, craft and design, Princeton Architectural Press, 2008

Frayling, Christopher, On Craftsmanship, toward a new Bauhaus, Oberon Books London, 2012

Adamson, Glenn, The Invention of Craft, Bloomsbury, 2013

Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, Penguin Books, 2008

Adamson, Glenn (ur.), The Craft Reader, Berg, 2010

Pallasmaa, Juhani, Misleča roka: eksistencialna in utelešena modrost v arhitekturi, Studia Humanitatis, Ljubljana, 2009

Pallasmaa, Juhani, Oči kože, arhitektura in čuti, Ljubljana, 2007

1. Lidewij Edelkoort je svetovno priznana napovedovalka trendov. Več o njej in njenih tekstih o trendih, oblikovanju pa tudi vlogi rokodelstva v sodobnem času si lahko preberemo na njeni socialnomedijski platformi: http://www.edelkoort.com/trendtablet/

2. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Handmade -When Design and Craft meet, 2013, dostopno na: http://www.trendtablet.com/4810-handmade/ (26.2.2014)

3. 'Indie' je okrajšava za 'indipendant' , lahko bi zapisali tudi 'neodvisna rokodelska skupnost'.

4. DIY je angleška kratica za: Do It Yourself, slovensko naredi si sam

5. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Crafts, a matter of scale and pace, 2014, dostopno na: http://www.trendtablet.com/29499-crafts-a-matter-of-scale-and-pace/ (26.2.2014)

LITERATURA:

Levine,Faythe in Heimerl, Cortney (ur.), Handmade nation: the rise of DIY, art, craft and design, Princeton Architectural Press, 2008

Frayling, Christopher, On Craftsmanship, toward a new Bauhaus, Oberon Books London, 2012

Adamson, Glenn, The Invention of Craft, Bloomsbury, 2013

Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, Penguin Books, 2008

Adamson, Glenn (ur.), The Craft Reader, Berg, 2010

Pallasmaa, Juhani, Misleča roka: eksistencialna in utelešena modrost v arhitekturi, Studia Humanitatis, Ljubljana, 2009

Pallasmaa, Juhani, Oči kože, arhitektura in čuti, Ljubljana, 2007

Although modern design is a relatively young profession in human history, tracing back to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, it has already gone through many stages of development - from the production of the first serial products to virtual design. The design has acquired a sense of function, decoration, form, material, colour, name, logo and brand. Products are produced and sold on a global market that appears to be a world of endless possibilities and ever-new, even better products. The design of the ‘new’ has expanded and become insatiable, especially in recent decades. The world is filled with products offering new experiences, often without real content and character. One of the world’s most famous trend forecasters, Lidewij Edelkoort (1), says that today, more than ever, design needs reflection - a reconsideration of the (non)meaning of design, and this reflection must include humanity. For her, craftsmanship and handmade products represent possible alternatives that many designers and artists are returning to in their creative processes (2).

Lidewij Edelkoort wrote these words in 2014, several years before the COVID-19 pandemic. The increasing use of digital media, virtual fantasy worlds and artificial intelligence, which experienced exponential growth during the pandemic, triggered a tactile revolution, a need for handcraft work and a revival of the experience of form and volume through physical touch – a sensitive mechanism for perceiving the world with our hands.

The popularisation of the ‘new wave’ of handicrafts began in the United States as early as 1994. Today, it represents the so-called ‘indie craft scene’ (3), a peculiar mix of traditional handcraft techniques, punk culture, DIY (4) ethos, modern aesthetics, politics, feminism and art. The movement, which has become global, is, in essence, strongly connected to the community - whether local or via the World Wide Web - which often triggers new economic relations and a lifestyle based on creativity and networking. Andrew Wagner notes that handicraft is not only about the production method and the quality of time and effort invested in creating the product but can also have a political voice (Wagner, 2008, 3).

Handiwork, its resumed quality, has been praised and recognised in the last twenty years also because of a bunch of so-called ‘Slow’ movements, from which the Slow Design movement emerged. The term was coined by Alistair Fuad-Luke in 2002. The movement considered a holistic approach to design and, as it has done many times before in the history of design, committed to a work process that takes into account the well-being of man, society and the environment. Additionally, the movement extended beyond the creation of physical products to non-material design, to the design of processes, services, experiences and organisations, and is currently moving towards the field of dematerialisation. The global recession of 2008, among other things, led to a re-evaluation of the values, design processes, and marketing possibilities of the products. These are no longer conditioned only by orders from larger companies and brands but are starting to appear from the hands of smaller design studios and craft businesses, and often emerge from the needs of the community. Handicraft, the incorporation of the handwork into making the finished product, plays a significant role here. It is no longer only a part of the experimental creation of a new idea but is integrated into the production itself. The human hand gains new power and becomes part of the tool. Or, as Juhani Pallasmaa poetically writes: “... When an axe or a sheath knife is being used, the skilled user does not think of the hand and the tool as different and detached entities; the tool has grown to be a part of the hand, it has transformed into an entirely new species of organs, a tool-hand.” (Pallasmaa, 2009,54).

The book On Craftsmanship Towards a New Bauhaus by author Christopher Frayling begins with the statement that craftsmanship became fashionable during the last few recessions, so we need to redefine and evaluate this term in today’s context (Frayling, 2010, 7). Craftsmanship, especially textile handcraft techniques, are becoming (once again) important in times of climate, migration and post-pandemic economic crisis in which we live today and in which the new generation Z is trying to find its place on Earth, to find opportunities to not only to survive but also to creatively co-create a future that does not lose touch with tradition.

During the period when we were forced to conduct creative pedagogical processes of guided mentoring at the undergraduate and graduate programmes in the courses Textile Design ‘remotely’, we were cut off from physical contact with the textiles that were created by the hands of the students, despite this we witnessed the newly emerging natural rhythm of home-made fabric, knitting, crochet, which encourages ‘slow’, hand-made production, makes sense of the possibilities of small-batch production and offers new ways of product promotion. We have paved the way anew for sustainable design, ecology and local production; we have returned to natural materials, organic dyes, post-treatments, artisanal knowledge and traditional production techniques. The individual’s creativity has not waned; on the contrary, the overlooked handwork with thread, yarn and textiles has been rediscovered and recognised anew, like the landscape view when the vehicle stops and we get out of it. This experience has undoubtedly left its mark on the genes of this ‘COVID-19’ generation of students. Every challenging experience provides opportunities to reassess established operation patterns and make necessary changes.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Lidewij Edelkoort is a world-renowned trend forecaster. You can read more about her and her texts about trends, design and the role of craftsmanship in modern times on her social media platform: http://www.edelkoort.com/trendtablet/

2. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Handmade -When Design and Craft meet, 2013, http://www.trendtablet.com/4810-handmade/ (accessed 26.2.2014)

3. ‘Indie’ is an abbreviation for ‘independent’; we could also write ‘independent craft community’.

4. DIY is an abbreviation for do-it-yourself

5. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Crafts, a matter of scale and pace, 2014, http://www.trendtablet.com/29499-crafts-a-matter-of-scale-and-pace/ (accessed 26.2.2014)

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

1. Levine, Faythe in Heimerl, Cortney (ur.), Handmade nation: the rise of DIY, art, craft and design, Princeton Architectural Press, 2008

2. Frayling, Christopher, On Craftsmanship, toward a new Bauhaus, Oberon Books London, 2012

3. Adamson, Glenn, The Invention of Craft, Bloomsbury, 2013

4. Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, Penguin Books, 2008

5. Adamson, Glenn, The Craft Reader, Berg, 2010

6. Pallasmaa, Juhani, Misleča roka: eksistencialna in utelešena modrost v arhitekturi, Studia Humanitatis, Ljubljana, 2009

7. Pallasmaa, Juhani, Oči kože, arhitektura in čuti, Ljubljana, 2007

Lidewij Edelkoort wrote these words in 2014, several years before the COVID-19 pandemic. The increasing use of digital media, virtual fantasy worlds and artificial intelligence, which experienced exponential growth during the pandemic, triggered a tactile revolution, a need for handcraft work and a revival of the experience of form and volume through physical touch – a sensitive mechanism for perceiving the world with our hands.

The popularisation of the ‘new wave’ of handicrafts began in the United States as early as 1994. Today, it represents the so-called ‘indie craft scene’ (3), a peculiar mix of traditional handcraft techniques, punk culture, DIY (4) ethos, modern aesthetics, politics, feminism and art. The movement, which has become global, is, in essence, strongly connected to the community - whether local or via the World Wide Web - which often triggers new economic relations and a lifestyle based on creativity and networking. Andrew Wagner notes that handicraft is not only about the production method and the quality of time and effort invested in creating the product but can also have a political voice (Wagner, 2008, 3).

Handiwork, its resumed quality, has been praised and recognised in the last twenty years also because of a bunch of so-called ‘Slow’ movements, from which the Slow Design movement emerged. The term was coined by Alistair Fuad-Luke in 2002. The movement considered a holistic approach to design and, as it has done many times before in the history of design, committed to a work process that takes into account the well-being of man, society and the environment. Additionally, the movement extended beyond the creation of physical products to non-material design, to the design of processes, services, experiences and organisations, and is currently moving towards the field of dematerialisation. The global recession of 2008, among other things, led to a re-evaluation of the values, design processes, and marketing possibilities of the products. These are no longer conditioned only by orders from larger companies and brands but are starting to appear from the hands of smaller design studios and craft businesses, and often emerge from the needs of the community. Handicraft, the incorporation of the handwork into making the finished product, plays a significant role here. It is no longer only a part of the experimental creation of a new idea but is integrated into the production itself. The human hand gains new power and becomes part of the tool. Or, as Juhani Pallasmaa poetically writes: “... When an axe or a sheath knife is being used, the skilled user does not think of the hand and the tool as different and detached entities; the tool has grown to be a part of the hand, it has transformed into an entirely new species of organs, a tool-hand.” (Pallasmaa, 2009,54).

The book On Craftsmanship Towards a New Bauhaus by author Christopher Frayling begins with the statement that craftsmanship became fashionable during the last few recessions, so we need to redefine and evaluate this term in today’s context (Frayling, 2010, 7). Craftsmanship, especially textile handcraft techniques, are becoming (once again) important in times of climate, migration and post-pandemic economic crisis in which we live today and in which the new generation Z is trying to find its place on Earth, to find opportunities to not only to survive but also to creatively co-create a future that does not lose touch with tradition.

During the period when we were forced to conduct creative pedagogical processes of guided mentoring at the undergraduate and graduate programmes in the courses Textile Design ‘remotely’, we were cut off from physical contact with the textiles that were created by the hands of the students, despite this we witnessed the newly emerging natural rhythm of home-made fabric, knitting, crochet, which encourages ‘slow’, hand-made production, makes sense of the possibilities of small-batch production and offers new ways of product promotion. We have paved the way anew for sustainable design, ecology and local production; we have returned to natural materials, organic dyes, post-treatments, artisanal knowledge and traditional production techniques. The individual’s creativity has not waned; on the contrary, the overlooked handwork with thread, yarn and textiles has been rediscovered and recognised anew, like the landscape view when the vehicle stops and we get out of it. This experience has undoubtedly left its mark on the genes of this ‘COVID-19’ generation of students. Every challenging experience provides opportunities to reassess established operation patterns and make necessary changes.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Lidewij Edelkoort is a world-renowned trend forecaster. You can read more about her and her texts about trends, design and the role of craftsmanship in modern times on her social media platform: http://www.edelkoort.com/trendtablet/

2. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Handmade -When Design and Craft meet, 2013, http://www.trendtablet.com/4810-handmade/ (accessed 26.2.2014)

3. ‘Indie’ is an abbreviation for ‘independent’; we could also write ‘independent craft community’.

4. DIY is an abbreviation for do-it-yourself

5. Edelkoort, Lidewij, Crafts, a matter of scale and pace, 2014, http://www.trendtablet.com/29499-crafts-a-matter-of-scale-and-pace/ (accessed 26.2.2014)

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

1. Levine, Faythe in Heimerl, Cortney (ur.), Handmade nation: the rise of DIY, art, craft and design, Princeton Architectural Press, 2008

2. Frayling, Christopher, On Craftsmanship, toward a new Bauhaus, Oberon Books London, 2012

3. Adamson, Glenn, The Invention of Craft, Bloomsbury, 2013

4. Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, Penguin Books, 2008

5. Adamson, Glenn, The Craft Reader, Berg, 2010

6. Pallasmaa, Juhani, Misleča roka: eksistencialna in utelešena modrost v arhitekturi, Studia Humanitatis, Ljubljana, 2009

7. Pallasmaa, Juhani, Oči kože, arhitektura in čuti, Ljubljana, 2007